Why Do Some Bibles Have More Books Than Others?

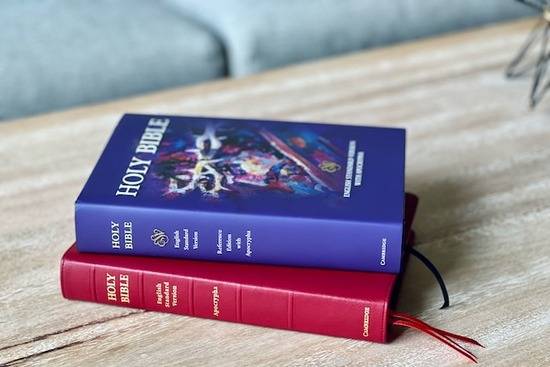

Christians consider the Bible as their sacred writings. But within Christianity, different denominations use Bibles with different numbers of books.

The Protestant Bible, which has 66 books, is the most widely used in the Christian world. But what about other Bibles, such as the Hebrew Bible or the Catholic Bible, used by other groups?

Each of these groups has reasons for using the Bible they use and for including the various books in it that they do. On this page, we’ll explore these different Bibles, the books they contain, and what these books are all about. By the end, you’ll have the knowledge and information to know which Bible is best for you.

We’ll answer the following questions:

- Why do different Bibles have different numbers of books?

- What are the different Bibles, and which books do their canons contain?

- Which Bible is the best choice, and how can I know it’s trustworthy?

Let’s begin!

Why do different Bibles have different numbers of books?

Photo by Carl Beech on Unsplash

Different Bibles have different numbers of books because at various points in history, groups of Bible believers decided what books should be considered as Scripture.

As you probably know, the Bible is “a book made of books.”

It’s a compilation of separate sacred books (or scrolls in ancient times). And the collection of these sacred books that make up the Bible is called the biblical canon.

Through the ages, the books that comprise the biblical canon have been the subject of debate in the Christian world. The result is different canons for different groups. Some contain more or less books. For example:

- The Hebrew Bible—22 books (all Old Testament)

- The Septuagint—80 books (53 Old Testament, 27 New Testament)

- The Catholic Bible—73 books (46 Old Testament, 27 New Testament)

- The Eastern Orthodox Bible—79 books (52 Old Testament, 27 New Testament)

- The Protestant Bible—66 books (39 Old Testament, 27 New Testament)

As you can see, all the Bibles with the New Testament have 27 books for it. This means that the Scriptural authority of the New Testament books was settled upon earlier, and any difference in the number of books of the different Bibles comes from the Old Testament.

So before looking at the various canons (and the differences in their Old Testaments), let’s see how the New Testament Canon was agreed on.

The New Testament canon

Photo by Tim Wildsmith on Unsplash

The New Testament books were viewed as Scripture from the time they were written. That’s why the apostle Peter, a contemporary of Paul, referred to Paul’s writings as Scripture in 2 Peter 3:16, just barely after they were written. But the books in the New Testament canon were formally agreed upon in the fourth century A.D. This happened in the form of an accepted consensus that came about gradually over the centuries.

Unlike the formality and controversies that characterized the establishment of the various Old Testament canons, this decision was free from controversy.

Before this decision, other books had been circulating. Books such as the Didache, the Apocalypse of Peter, the Shepherd of Hermas, the Epistle of Clement, the Epistle of Barnabas, and the Gospel of Thomas.

But they were eventually excluded from sacred Scripture. The reasons included:

- They were not written by the apostles.

- They had shallow spiritual content.

- They outrightly contradicted the already established canon of Scripture.

While some were completely discarded, others were deemed useful and retained as non-scriptural reads for believers.

Finally, Athanasius, the bishop of Alexandria, wrote in his A.D. 367 Easter Letter a list of New Testament books that he regarded as Scripture. This list contained the books of the New Testament as we know them today:

- The Gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, John

- The Acts of the Apostles

- The Pauline Epistles—Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 and 2 Thessalonians, 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon, Hebrews

- The General Epistles—James, 1 and 2 Peter, 1, 2, and 3 John, Jude

- Revelation

This list was accepted by church councils in Rome in A.D. 382, then in Hippo in A.D. 393. The Council of Carthage officially adopted it in A.D. 397.1

So as you can see, the number of books in the New Testament canon was sealed very early on. And the difference in the total number of books in the different Bibles comes from the Old Testament.

To understand why this is the case, we’ll look at each of the Bibles and their histories.

What are the different Bibles and which books do their canons contain?

Throughout history, Bible believers have had a set of books that they consider to be the authoritative Word of God—starting with the Ancient Jews all the way to Christians today. The different Bibles are:

- The Hebrew Bible

- The Septuagint

- The Latin Vulgate and Catholic Bible

- The Protestant Bible

- The Eastern Orthodox Bible

In this section, we’ll look at the different Bibles and the circumstances that led to them having the number of books they have.

Let’s begin with the earliest to exist.

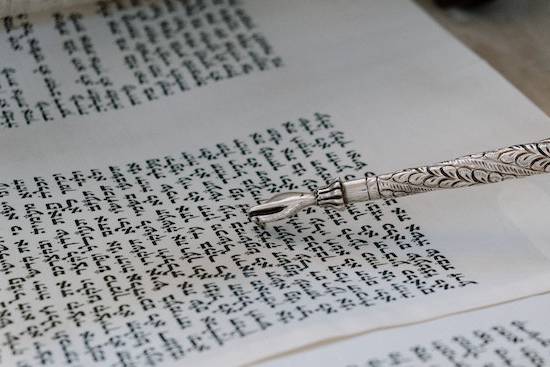

The Hebrew Bible

Photo by cottonbro studio

The Hebrew Bible or the Tanakh was the Scriptures used by the Israelites. It contains 24 books of the Old Testament. The books are divided into 3 sections:

- The Torah or the Law (5 books)—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy

- The Nevi’im or Prophets (8 books)—Joshua, Judges, Kings, Samuel, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, the Twelve (all the 12 books of the minor prophets as one book)

- The Ketuvim or Writings (11 books)—Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Songs of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Chronicles, and Ezra and Nehemiah (as one book)

While it’s not exactly clear when the 24-book Jewish canon was fixed, most scholars and historical records point to its compilation by Ezra and other Jewish scribes in Jerusalem in the years after the Babylonian captivity.

The Talmud—the main writings of Jewish religious laws—affirms that the compilation was finished in 450 B.C. and that it’s never changed since then.2

Future Jewish writings, like the commentary on the book of Ecclesiastes called Midrash Koheleth, mentions the fixedness of the 24-book canon when it states that bringing together more than 24 books causes confusion.3

Scripture also makes it clear that by the time of Jesus Christ, the Hebrew Bible was the accepted canon. Jesus Himself referred to it in Luke 24:44 when He spoke about the “Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms” (NKJV). In this case, the Psalms was probably equivalent to the Writings.

Both Jesus and other New Testament writers refer to the Scriptures and heavily quote the Old Testament writings.4 But after the time of Jesus, other books were considered for the Old Testament canon.

The Septuagint

Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash

The Septuagint is the Greek translation of the Old Testament and contains 53 books. It was meant for the Hebrews scattered in the Greek-speaking world of the eastern Roman Empire since Hebrew and Aramaic, the languages of the Old Testament, were no longer commonly used in the Hellenistic era.5

The 53 books include all 24 books of the Hebrew Bible plus 14 other books. The 24 books from the Hebrew Bible are organized and named in a different manner to make them 39 books, though the content is the same.6

These are the changes that made 39 books out of the 24:

- The book of the Twelve is separated into the individual minor prophets, making twelve books instead of one.

- The books of Kings, Samuel, and Chronicles are each split into two—1 and 2 Kings, 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Chronicles—making six books instead of three.

- The books of Ezra and Nehemiah are separated, making them two instead of one.

The extra 14 books were Greek texts written between the third century B.C. and the first century A.D.—after the last book of the Jewish canon was written.

They include:

- Whole books—Tobias (or Tobit), Judith, Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus (or Sirach), Baruch, 1, 2, and 3 Maccabees, Esdras 1, Prayer of Manasseh, and Letter of Jeremiah

- Additions to the book of Daniel (each classified as a book)—The prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Holy Children, Susanna and the Elders, Bel and the Dragon

- Additions to the book of Esther (not classified as a book)—Esther 10:4-13, Esther 11-16

- An addition to the book of Psalms (not classified as a book)—Psalm 151

- An appendix (not classified as a book)—4 Maccabees

Though the Jews and the New Testament writers never considered these books as Scripture, many saw them as useful and read them often.

Photo by Tim Wildsmith on Unsplash

Some like 1 and 2 Maccabees are historical accounts covering events between the end of the Old Testament canon and the coming of Jesus. And others like Judith contain fictional writings that teach godly values. So, when the Jewish canon was translated to Greek to form the Septuagint or LXX, these extra books were also added to it.

Later on, these extra books became known as the Apocrypha or the Deuterocanon.

Though both words often refer to the same set of books, Apocrypha is used by those who don’t consider the books to be divinely inspired or have scriptural authority. It implies that they’re not canonical. On the other hand, the word Deuterocanon is used by those who accept them as Scripture. And as we’ll see later, some Bibles have all or some of these books as deuterocanonical.

Back in the first century A.D., the Septuagint (that included the extra books) was widely used by Jews and Jewish Christians. And it was adopted by the early church as their Old Testament. Then, in A.D. 90, Jewish rabbis met at the Council of Jamnia and decided that only the 39 books of the Jewish canon make up the Old Testament canon.7

Despite this decision, the mainstream Christian Church continued using the Septuagint (including the 14 extra books) as their Scriptures throughout the eastern Roman Empire.

But for the church in the western Roman Empire, the Latin Vulgate became the main Bible.

The Latin Vulgate and Catholic Bible

Photo by James Coleman on Unsplash

In the fourth century A.D., Pope Damasus commissioned Jerome to provide a Latin Bible for the Latin-speaking church on the western side of the Roman Empire. Thus was born the Latin Vulgate in A.D. 405.

Rather than translating from the Septuagint, Jerome translated most of the text directly from the Hebrew Bible. He included all the books of the Jewish canon as the Old Testament, and though he acknowledged the importance of the extra 14 books, he designated them as apocryphal and proposed that they be considered noncanonical.

But the church didn’t accept his proposal, and most of the extra books were included in the Bible as the Deuterocanon at the Council of Rome in A.D. 382.

Even so, they excluded:

- The Prayer of Manasseh

- Esdras

- 3 Maccabees

- The 4 Maccabees appendix

- The extra chapter in the book of Psalms (Psalm 151)

Though 11 of the 14 books were kept, only 7 books actually appear (Tobit, Judith, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach, 1 and 2 Maccabees, Baruch).

Why? For three reasons:

- Three of the other books (Susanna, Bel and the Dragon, and the Song of the Three Holy Children) are part of the book of Daniel.

- The Letter of Jeremiah is included in the book of Baruch.

- The extra chapters and verses of Esther are included in the book of Esther.

This Bible was not immediately accepted by the church. But by the sixth century, it was the most commonly used Latin Bible in the Roman Empire.

Photo by Wim van ‘t Einde on Unsplash

And it remained so until the Protestant Reformation..

When Martin Luther translated the Latin Bible into the German language in 1534, he separated the extra books from the Hebrew Old Testament, placing them between the Old and New Testaments. That’s why they’re also referred to as Intertestamental Books. They were designated as apocryphal at this time.8

He cited the following reasons for this decision:

- The writers of these books themselves don’t say they’re inspired—they are silent about the inspiration of the books they wrote.

- Future Bible writers of the New Testament didn’t refer to them as Scripture, unlike the way they refer to the Hebrew canon.9

- They taught teachings that contradicted the already established Scriptures, like:

- Giving money to atone for sins (Sirach 3:30; Tobit 4:10).

- Praying to the dead (2 Maccabees 12:43-45).

- Praying to saints and asking them for prayer (2 Maccabees 15:12-16).

In response to Luther’s protests, the church declared the Latin Vulgate to be the official Bible of the Roman Catholic Church at the Council of Trent in 1546.10 With this, they decided they needed an official edition of the Vulgate.

Theologian Sixtus of Siena began revising it and in 1566, he coined the term deuterocanonical, meaning “second canon,” to refer to the new canon that was not part of the original Hebrew Bible that had been accepted as canonical.

When the new edition was ready, Pope Clement VIII commissioned the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate as the official Bible of the Roman Catholic Church in 1592. He also added three of the excluded apocryphal books: the Prayer of Manasseh and 3 and 4 Esdras. This brought the Latin Vulgate to a total of 76 books. And this has been replicated in all future versions and translations of the Vulgate.

In 1582, the Catholic Church allowed for the translation of the Vulgate to English, and the Douay-Rheims Bible was published in 1609-10 as the first Catholic English translation.

This became the predecessor of later Catholic Bibles.

Meanwhile, Martin Luther’s Bible acted as the predecessor of Protestant Bibles that didn’t include the deuterocanonical books in the body of Scripture but rather separated them and designated them as the Apocrypha.

The Protestant Bible

Photo by Tim Wildsmith on Unsplash

At first, the Protestant Bible contained 80 books. But later, the Apocrypha was excluded altogether, so only 66 books remained, as is common today.

As we saw earlier, it all started with Martin Luther’s Bible. This Bible had a total of 80 books since the three extra books in Daniel and the extra verses and chapters included in Esther in the Vulgate were labeled as separate books.

Later, when the Bible was translated into English to form the Geneva Bible, the new Bible followed Luther’s model, ending up with an 80-book Bible, too.

And when the King James Bible was commissioned in 1611 in Protestant England, it also had 80 books like Luther’s Bible, including the intertestamental Apocrypha. The only difference was that the books 3 and 4 Esdras were named as 1 and 2 Esdras.

All future Protestant versions followed this model until the mid-1800s.

In 1855, a decision was made to leave out the Apocrypha in the publication of Protestant Bibles. Since it was deemed as less important, why not cut publication costs by removing it altogether? Since then, the majority of Protestant Bibles have 66 books with a 39-book Old Testament.

But there are some Protestant denominations that still use Bibles with the Apocrypha. Like the Anglican Communion, the Episcopal Church, the United Methodist Church, and the Lutheran Church. And other Bible believers view the Apocrypha as inspired. An example is the Orthodox Church that even has more books in its Deuterocanon than the Catholic Bible. More on that next.

The Eastern Orthodox Bible

Photo by Mikhail Nilov

The Orthodox Bible is used by the Eastern Orthodox Church, which traces its origin to the churches established by the apostles in the eastern Mediterranean region.

When in the fourth century A.D., Constantine made Constantinople the capital of Rome and Christianity the official religion of the empire, the leadership of the Christian world mostly came from the Greek church fathers in the east.

But when both political and religious power shifted to Rome, the church in the east gradually separated from the mainstream Roman Catholic Church. They formed the Orthodox Catholic Church or the Eastern Orthodox Church.

And they have their own Bible—the Orthodox Bible.

The Orthodox Bible is the largest Bible. While it has all the Catholic deuterocanonical books as part of its canon, it also retains all the books in the Septuagint that were left out of the Latin Vulgate.

They include:

- Prayer of Manasseh

- 3 Esdras (Written as 1 Esdras)

- 4 Esdras (Written as 2 Esdras)

- 3 Maccabees

- 4 Maccabees as an appendix

- Additions to Psalms—Psalm 151

Apart from the mainstream Eastern Orthodox Church, there are also other Orthodox churches that have even more books in their canons.

These include the Oriental Ethiopian, Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo, the Coptic Orthodox, and Syriac Orthodox canons that are all different from each other.

With all these Bibles, and the various reasons for including and excluding different books, how can you know which Bible to use?

Which Bible is the best choice, and how can I know it’s trustworthy?

Photo by Sixteen Miles Out on Unsplash

A safe place to begin is to embrace the books of the Bible that have had the least controversy over their place in the Bible—those that are generally accepted as part of inspired Scripture. From what we’ve seen, the Jewish Canon and the New Testament Canon pass this test.

Concerning the Jewish Canon, Paul writes in the New Testament that the Jews “were entrusted with the very words of God” (Romans 3:2, CSB).

So these 66 books of the Bible can be trusted as God’s Word, since from the very begining, their scriptural authority and inspired origin has been acknowledged. And for that reason, the 66-book Protestant Bible is considered trustworthy by all since its contents are included in all the other Bibles.

When it comes to the other books in the Apocrypha/Deuterocanon, we all have to decide whether to believe them.

That’s a decision best made after taking the time to read the books.

A couple questions you can ask yourself as you read are:

- Do they agree in principle with the teachings of the Hebrew and New Testament canon?

- Do the writings themselves claim inspiration as the writings of the Hebrew and New Testament canon do?

The Bible guides us to God and His love

Whatever conclusion we come to regarding some the apocryphal/deuterocanonical books, we can be grateful for the many books of the Bible—both in the Old and New Testaments—that are undisputed. Books from which we can draw spiritual nourishment. And books that so clearly reveal the love of God for us.

These books can be our foundation for testing all other books to see whether they also reflect this character of God.

As you embark on a journey of understanding the history of God’s Word, you’ll come to appreciate His goodness in preserving this “good book” throughout the ages to guide us to Him and His love.

Related Articles

- Livingstone, E. A.; Sparkes, M. W. D.; Peacocke, R. W., eds. 2013 Oxford University Press. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. p. 90 [↵]

- Bava Batra 14b–15a, Rashi to Megillah 3a, 14a. [↵]

- Midrash Qoheleth 12:12 [↵]

- Matthew 4:4 cites Deuteronomy 8:3; Romans 1:17 cites Habakkuk 2:4; 1 Corinthians 1:19 cites Isaiah 29:14; Acts 13:33 cites Psalms 2:7; Romans 3:10-12 cites Psalms 14:1-3; Romans 3:13 cites Psalms 5:9 and Psalms 140:3; Romans 3:14 cites Psalms 10:7; Romans 3:15-17 cites Isaiah 59:7-8; Romans 3:18 cites Psalms 36:1. [↵]

- “Septuagint,” New World Encyclopedia. [↵]

- Ibid. [↵ ]

- Jack P. Lewis 2002 The Canon Debate. “Jamnia Revisited.” In L. M. McDonald; J. A. Sanders (eds.). The Canon Debate. [↵]

- “What Is the Apocrypha?” Christianity.com. [↵]

- Ibid. [↵]

- Ibid. [↵]

Questions about Adventists? Ask here!

Find answers to your questions about Seventh-day Adventists

Didn’t find your answer? Ask us!

We understand your concern of having questions but not knowing who to ask—we’ve felt it ourselves. When you’re ready to learn more about Adventists, send us a question! We know a thing or two about Adventists.